Lately I’ve been playing with technology to have fun, try out new things and deepen my knowledge of new frameworks and technologies. So I created a Lab section on my website where I will share anything fun that I build.

My latest experiment revolved around what’s necessary to build and run self-hosted AI models in production as well as to how to capture realistic data to help them improve. I thus created a Connect 4 game in two versions. First, a player goes against an AI model. You can see the initial training process here.

I selected Connect 4 because algorithmic searches for the next move are sufficiently complex to be slow, and designing a heuristic that mimics advanced strategies presents a significant challenge—particularly because finding the global maximum is difficult.

I would like to say that even though thet model, plays well, it’s still considered “easy mode.” As it doesn’t “trick” the opponent with any smart strategies like humans do.

In order to gather realistic data for my model to learn I decided to create a live-play version where humans could play against each other. This way I can capture what moves they decide to make and fine-tune my model into a more difficult version.

To create this, I first considered the tools available to me and how I could use them to provide my users with a real-time experience. Here’s how I approached it.

Deployment Environment

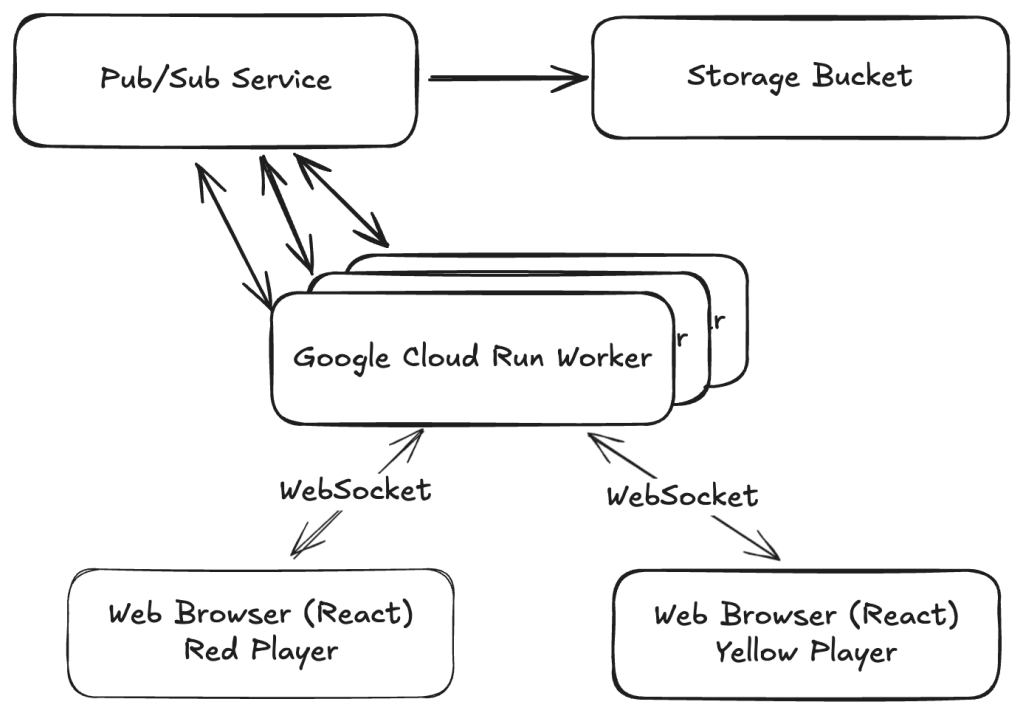

My deployment environment consists of the free tools I get in Google Cloud Platform, for this game I use three components:

- Google Cloud Run – To run my webapp.

- Pub/Sub Topics – to deliver messages reliably across multiple workers.

- Storage Buckets – To save my training examples.

These tools ended up being enough to produce a good real-time user experience, at the same time made it easy for me to capture information.

Solution Architecture

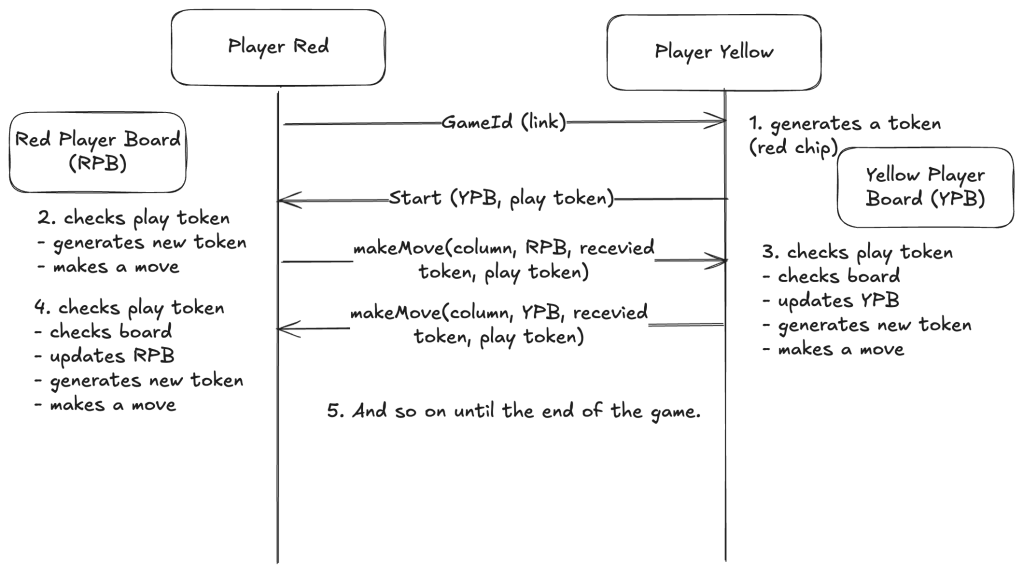

To make this solution work – given I’m not using a database – I designed a protocol so both players could keep the state jointly. I got inspired by a classic Seinfeld scene where Kramer and Newman are playing risk. I’ll cover the protocol in the next paragraphs but first let’s talk about the deployment architecture.

One nice feature of Google Cloud Run (as opposed to other serverless providers) is that it fully supports WebSockets; connections can live up to one hour, which is plenty for my Connect 4 game. Even if we needed connections to last longer, it’s just a matter of implementing a reconnection strategy.

One potential problem to overcome with this architecture is that the two players might end up in different workers making it impossible to play directly. This is where pub/sub comes into play. Every worker connects to the same pub/sub topic and every websocket message gets broadcasted across them. When a client connects, it tells the worker the gameId they’re connecting to, and the worker can then decide if it has to process or not the messages it receives from the queue, making the solution resilient and even if a client drops and gets reconnected to another worker it will still work.

Once we have the communication channel sorted out, the next problem to address is the communication and managing the board state correctly so the following conditions are met:

- We don’t allow one player taking over the other player’s turn.

- No more than two players can partake a game.

- No player has complete control over the board.

- No player that knows JavaScript can tamper with the game to cheat.

This is where the Kramer and Newman analogy comes to play. Imagine two players that don’t trust each other at all and are afraid that the other player would tamper with the board. To this end, each player would take all of the opponent’s chips and give them exactly one chip to play on each turn, and once a turn is taken, whoever gave the chip verifies that the chip played was truly given by them. To illustrate further here is an example sequence.

- Player red (player 1) creates a blank board. – And shares the link with player yellow (two).

- Player yellow then joins using the link, and sends a red chip to player red.

- Player red then takes a turn, and sends the board to player yellow, along side a yellow chip for them to play.

- Player yellow then verifies that the board has the red chip they gave, plays the chip they received, and sends the board to player red alongside a red chip.

- Player red also verifies that the board has the yellow chip they gave, plays the chip they received, and sends the board back to player yellow alongside a yellow chip.

- This pattern continues until any one player wins or the board is full.

In the real implementation, the only difference (since we’re not in the physical world) is that each player keeps a copy of the board and updates it with the other player’s move, but also verifies consistency with the board received from the other player. This way if one player changes their board before sending it, the other doesn’t just trust and move on but verifies that nothing is different from what they would expect.

The last step is capturing data for training purposes. GCP’s Pub/Sub topics are useful here, serving a dual function. I set up a subscription to batch message payloads by time (in JSONL format) and save them to a bucket. This allows me to access the data from a Google Colab notebook to train my model.

Closing Thoughts

This game is a simple proof of concept that demonstrates the fundamental techniques needed to build larger live collaboration tools or chatrooms at scale. It also shows how strategically capturing data can empower machine-learning models to eventually outperform humans by leveraging the collective wisdom of crowds.

Leave a comment